By Heather Monahan

Assistant Features Editor

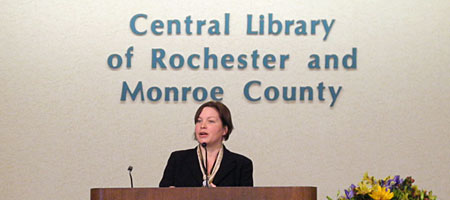

Sonja Livingston discusses her unconventional childhood in her book, “Ghostbread.”

“I know where I came from,” Livingston said in “Ghostbread.”

Her childhood struggles with poverty helped her become who she is today, and she doesn’t forget that.

Livingston visited St. Bonaventure Monday night to speak to students and staff as well as members from the community in the Walsh Amphitheater. Livingston discussed her book, a series of 122 chapters, or what Livingston likes to call, snapshots of her childhood.

“(The) chapters are very short,” Livingston said. “The book is written in a bunch of little snapshots. I was writing short little bits because the memories came to me in short little bits.”

The 122 memories which make up the book encompass memories surrounding Livingston’s childhood. In her youth, the author lived in poverty in Western New York. An Indian Reservation and a bad neighborhood in Rochester are two of the many places Livingston and her family called home.

Livingston was raised by a single mother and had two brothers and four sisters, most of whom were from different fathers. She never met her own father and never had a father figure in her life, so didn’t know much about father-daughter relationships.

“I know dads on TV are protective,” she said. “But any fathers I ever saw were scary.”

However, Livingston said her husband’s father is one of the sweetest men she’s ever met – just talking about him moved her to tears.

“Sometimes I think about him and I think what it would have been like to grow up with a dad who was very loving,” Livingston said.

Being raised in a neighborhood typically seen as “hidden” in the United States, Livingston grew up in very diverse cultural areas. She said in her experience, her family lived in places where white people were typically a minority. While she said race wasn’t as important, she did run into some trouble on the Tonawanda Reservation where she lived.

“There was a little girl on the reservation who kept saying she was going to beat me up because I was white,” Livingston said. “As a kid, that was really hard to understand but now, of course, I understand much better what was going on and why they might feel that way.”

According to Livingston, her writing experience came very naturally.

“I sometimes think that I wrote my story as an adult because as a kid, the way that I grew up was really embarrassing,” Livingston said. “I was embarrassed to be in the poor family. I was especially sensitive and kept things in.”

However, as she got older and began sharing her story, she realized she wasn’t the only one benefitting from publishing her past.

“I realized that not only was it a good experience for me to write (the memories) down, but that it seemed like people were learning something when they read my work,” she said. “I wrote about living in this certain neighborhood of Rochester, and people even in Rochester would read little pieces that I’d written and say ‘There’s no such neighborhood like that in Rochester.’”

Alexandra Henry, a senior gerontology major, admits Livingston changed her perspective on poverty.

“When I think about poverty, I think about New York City or really urban neighborhoods and high criminal rates and things like that,” Henry said. “But this is completely different.”

Henry said something that really stood out to her about Livingston’s story was Livingston’s determination.

“She had that inner motivation and a lot of people don’t have that,” Henry said. “They feel like they have to look elsewhere for that motivation to continue on and gain your success, but she actually found that within herself and that’s something people don’t have these days.”

While Livingston has moved on from her past and now lives a completely different life, she read the first line of her epilogue in “Ghostbread” and summed up how her past affects who she is now.

“The past is still there.”