By Kevin Rogers

Opinion Assignment Editor

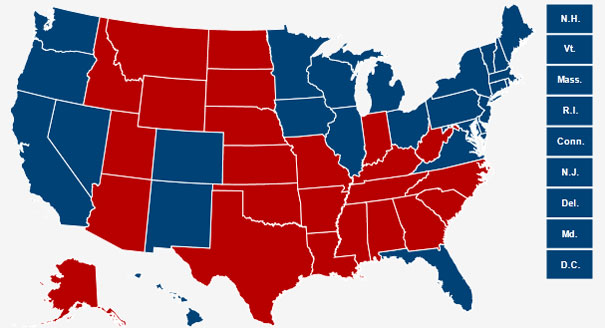

In media coverage of politics and elections, it’s common to hear the words “red state” and “blue state.” As President Barack Obama took the oath of office for the second time, Dr. Ben Gross of the sociology department looked to shine some light on the terms and what forms they take in newspapers.

On Jan. 21, Gross presented his analysis during a Faculty Research Colloquium presentation titled “Color Coding Politics: Creating meaning around ‘Red States’ and ‘Blue States’ in U.S. newspapers between 2003 and 2007.”

Gross started the research while working for his Ph.D. in sociology, analyzing 337 articles from newspapers across the nation during a four-year period. The period allowed him to analyze rhetoric before, during and after presidential elections.

“Political scientists, politicians and even the general public now are using red states and blue states to try to describe political affiliations,” Gross said. “My research wanted to look at how these [terms] map themselves within U.S. newspapers.”

Gross described media frames, the way in which media personnel present the news, saying that some subscribers often only accept the facts as they are presented in the framework.

“If you’re hearing a story about unemployment and they’re saying nothing about structural causes, people will tend to think that unemployment is only caused by personal choice or individual qualities,” Gross said. “People can and do reject frameworks, the frame works are suggestive. They’re critical to political discussion because they structure our ideas and reasoning.”

Gross described the six distinct frameworks he discovered in his study of newspaper articles. In the “Call for Unity” frame, writers urged citizens to put aside differences and practice civility in discourse. The “Purple State” frame diminished the media discussion of red states and blue states, arguing that the frame is too general. In this frame, writers suggest the red-blue divide is oversimplified and contest the notion that a state’s overall voting outcome represents the state’s dominant ideology.

“There’s a lot of variation in the geographic states,” Gross said. “This was a framework where people were openly saying ‘we don’t believe this red and blue state even exists. This is something that is really a fabrication.’”

In the “Lifestyle Stereotype” frame, writers discussed social and cultural differences between citizens in red states and blue states. This framework looked to align cultural preferences to political persuasions, Gross said.

“The assumption is that the red and blue divide is real and we can see it in everyday activities,” Gross said. “They’re reducing the American populace to vague caricatures they assume we could witness in everyday life.”

Two of the other frameworks were direct opponents. In the “Culture War” framework, conservative writers argued that liberals were out of touch with the average America. In contrast, the “Liberal Partisan” frame, the post-prevalent frame Gross found, opposed the culture war and looked to criticize conservative hypocrisy.

Gross called the final frame “How to Win.” Writers and analysts used heavy metaphors to discuss politics as a contest with points to be scored. This framework lent itself to a negative view of the political process and politicians, Gross said.

“It talked about politics as being a game,” Gross said. “The assumption in the framework is that politicians are insincere. They will say or do anything to put points on the board or win elections.”

During his research, Gross found that “Culture War” and “Liberal Partisan” frames surged during the 2004 election as pundits on both sides tried to establish opposition. The “Purple State” and “Lifestyle Stereotype” frames were more frequent outside the election season.

Though Gross focused on 2003 to 2007 in his analysis, he said he’s open to continuing his analysis to study newspaper frameworks in the Obama era.

“I’m thinking of revamping it as another publication to study 2008 to 2012 and make it a 10-year study,” Gross said.