By Kevin Rogers

Editor-In-Chief

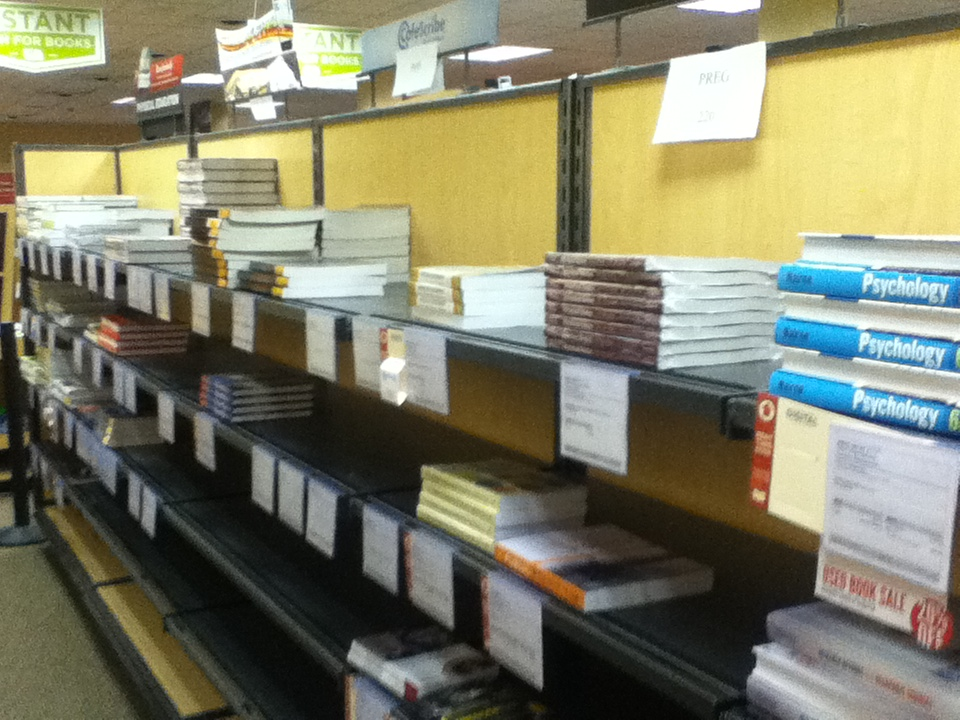

One of the more dreaded prospects for students at the beginning of a new semester is the inevitable textbook list that materializes a few weeks before classes begin. Once the books are purchased, some students question how useful the investment truly is.

“Textbooks are overpriced and underused,” Vivien Pat, a freshman biology major, said. “Professors shouldn’t assign textbooks unless they actually use the content in the textbook and if it’s helpful with exams and assignments.”

To support her claim, Pat said one of her classes last semester didn’t require her to use the assigned textbook.

“In chemistry, I passed the course in my first semester without opening the textbook once,” she said. “I bought the book, put it on my desk and it did not move all semester. It was $90. I know others have the same problem.”

Nancy Casey, chair of the elementary education department in the School of Education, said professors should see to it that textbooks are useful. In that case, however, students have to make stronger efforts to use their textbooks.

“I think it’s important for faculty to consider how they use textbooks,” she said. “If I assign a textbook and I never use it, that’s a shame and students should be upset. But I think it’s equally important for students to realize that in 150 minutes of class a week, I can’t possibly cover all of the material they need to know.”

Casey said she selects textbooks based on quality and how well they tie into her syllabus in each course.

“The textbook doesn’t drive the course. The syllabus drives the course,” she said. “If you have a good textbook that matches what you are supposed to be teaching in the class, then it becomes useful.”

Casey added she looks to pick textbooks that are readable and encourage more compelling classroom discussions. Casey said she requires students to read assigned texts before each class period, as she doesn’t solely discuss the readings in class.

“I look to make sure that it’s something students can engage with,” Casey said. “I do not lecture directly from the textbook. I teach the content, but I don’t teach the textbook.”

Mary Rose Kubal, director of the international studies program in the political science department, said she looks to pick textbooks that mesh with her course objectives and feature a writing style that students can comprehend. However, she said textbooks aren’t always perfectly linked with her class plans.

“I want to make sure that it lines up with the learning objectives that I have,” Kubal said. “Of course, they never do line up exactly. There are tradeoffs. Sometimes there’s a book that goes better with my objectives, but it’s a bit drier or more jargony.”

Kubal said she tries to add content beyond the book to her lectures but acknowledged the problem of falling into book-reliant lectures. However, she said students can’t rely solely on lecture notes to succeed in her classes.

“It’s a hard balance to strike, because you don’t want to give a lecture that’s the same material as the reading,” she said. “But then, you don’t want to not address what’s in the book. I assign readings from the book, and I do acknowledge the main points, because students should know what I think is important. It’s impossible to cover everything in the reading in 50 minutes or an hour and 15 minutes.”

Another factor Kubal considers in selecting textbooks is cost. She said she’ll occasionally assign a less-comprehensive textbook if there’s a significant difference in cost compared to a better-quality text.

“If it’s a $20 difference, I’ll probably go with the better book, but if it becomes a $50 difference, I’ve stopped using books,” she said. “It’s really hard for a book to be $50 better than another.”

Michael Russell, a professor of marketing in the School of Business, said he also considers cost when picking textbooks and attempts to assign cheaper books. However, Russell’s main concern when picking textbooks is how well they relate to his course material.

“I have selected soft-cover books in some cases to reduce the amount students pay,” Russell said. “The most important factor is relevancy to our curriculum and currency. Key issues and trends change often, so the book selected needs to be current.”

Kevin Vogel, a lecturer of biology, said he tries to keep textbook costs down, but for him, content trumps cost.

“I think faculty sincerely wish to keep the cost of texts to a minimum, if possible,” Vogel said. “I look for texts that have the greatest intersection with the topics I intend to cover in the course. If the text is that much better, I would grudgingly require that text.

Casey said cost is a consideration when she selects books for each semester, but it’s not nearly as important as the quality of the text.

“I look at cost, but I look more at the importance of what the textbook has,” she said. “Maybe that’s bad of me to say that, but if you need a textbook, you need a textbook. There are very few courses where you can get away without reading a textbook.”

Casey challenged students to make full use of their textbook investments, arguing they can expand their knowledge base, even if it’s not evidently necessary for the course.

“One of the things I value most about in a person, but more importantly in a student, is curiosity,” she said. “I think students should be curious enough to push themselves to use those textbooks and learn more about the content.”