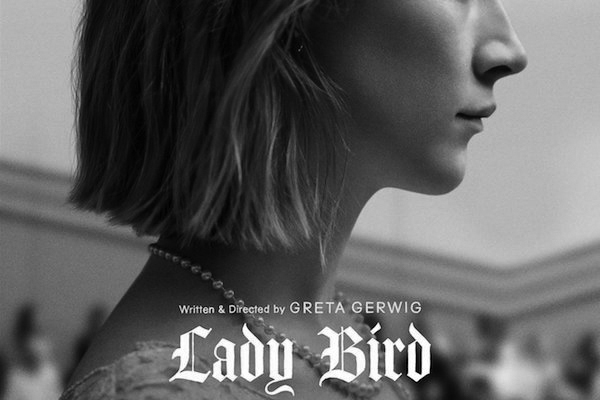

A 2018 Oscar nominee for Best Picture, Greta Gerwig’s “Lady Bird” is a candid revitalization of an otherwise dead plotline: the overcooked coming-of-age story, all about boys and booze, with a few familial frustrations scattered throughout.

Gerwig, the work’s screenwriter and director, is cunning in her approach – allowing a healthy dose of nostalgic clichés into the story. And, likely since the narrative is a self-invested depiction of her own development, “Lady Bird” further soars through the rocky 17-going-on-18 mindset in the most stripped-down light imaginable.

It’s that conflicting nature of self discovery that makes “Lady Bird” so astounding. The film follows Christine McPherson – donning the nickname Lady Bird throughout the film – as her youthful craving for uncharted adventure carries her through a senior year of firsts.

At face value, Lady Bird’s a spunky Sacramento-raised teen. And she’s everything you’d expect from a rising college freshman: assured, but still entirely contradictory.

Lady Bird finds the West Coast zeitgeist all too pretentious, but shamelessly indulges in undying (and, sometimes, undeserved) familial support.

She finds her Catholic school’s pro-life, sex education programming distasteful, but she’s still wrapped up in constant anxiety of “unspecial sex.” Despite her self-proclaimed artist identity, she struggles to commit to the school’s theatre production practices – mainly because a pair of bell-bottom pants, an occasional joint and a few bold statements will do.

Lady Bird gets high for the first time. She has her first sexual escapade and naturally falls in “love” – well for a few weeks, until she finds her short-term love interest kissing another boy in a public restroom. Really, Lady Bird shows us the teenager we all were and, somehow still have in us. She’s unsure of herself, but that’s equally evident in all her adult role models.

On a deeper tier than exploring the teenage psyche – for what it is and nothing more – “Lady Bird” manages to bleed into the pressures of surrounding adulthood: the financial burdens, moral debates, uncomfortable “sex talks” and everything in-between.

In the midst of closing her high school chapter, Lady Bird grapples with a recently laid off – and highly depressed – father and a seemingly caustic mother – working tirelessly to keep the family afloat and coping with the onset of empty nest syndrome. Through and through, viewers see Lady Bird’s burden on her family, her parent’s inability to communicate and begin to feel a level of normalcy in that dynamic.

It’s not until Lady Bird’s departure from that suburban nest – finally at college in New York City, the “home of culture” – that she grows an appreciation for her West Coast origins, as well as the drama of friends and virginity lost.

In a beautiful closing moment, she leaves her parents a voicemail after a night of drinking turned ER visit – only after walking out of the hospital, stumbling into a cathedral’s Sunday mass and, for the first time, feeling a taste of her beginnings.

Back on the city streets, mascara running down her face and donning last night’s clothes, she breathes appreciation for the first time, exclaiming, “Hi, mom and dad. It’s me, Christine. It’s the name you gave me; it’s a good one…Did you feel emotional the first time you drove in Sacramento? I did and I wanted to tell you, but we weren’t really talking when it happened. All those bends I’ve known my whole life and stores – the whole thing – I wanted to tell you [that] I love you. Thank you.”

It’s in that moment that Lady Bird, willingly “Christine” for the first time, experiences a primary mark of adulthood: accepting the past in the wake of beginning the future.