Guillermo del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” is a compelling drama that, like water itself, fluidly moves through an evocative plotline, while captivating viewers by offering deep connections to the numerous protagonists within the work. Each character holds relatable, timely and pained stories of their own.

Set in 1962 Baltimore, the film – which won “Best Picture” at the 2018 Academy Awards – follows Elisa Esposito, a lonely, mute woman, working in a high-security government laboratory. Assigned to the most highly protected area of the facility, Elisa encounters what marine biologist Dr. Robert Hoffstetler calls the most sensitive specimen ever housed in the laboratory: A South American, water-dwelling creature.

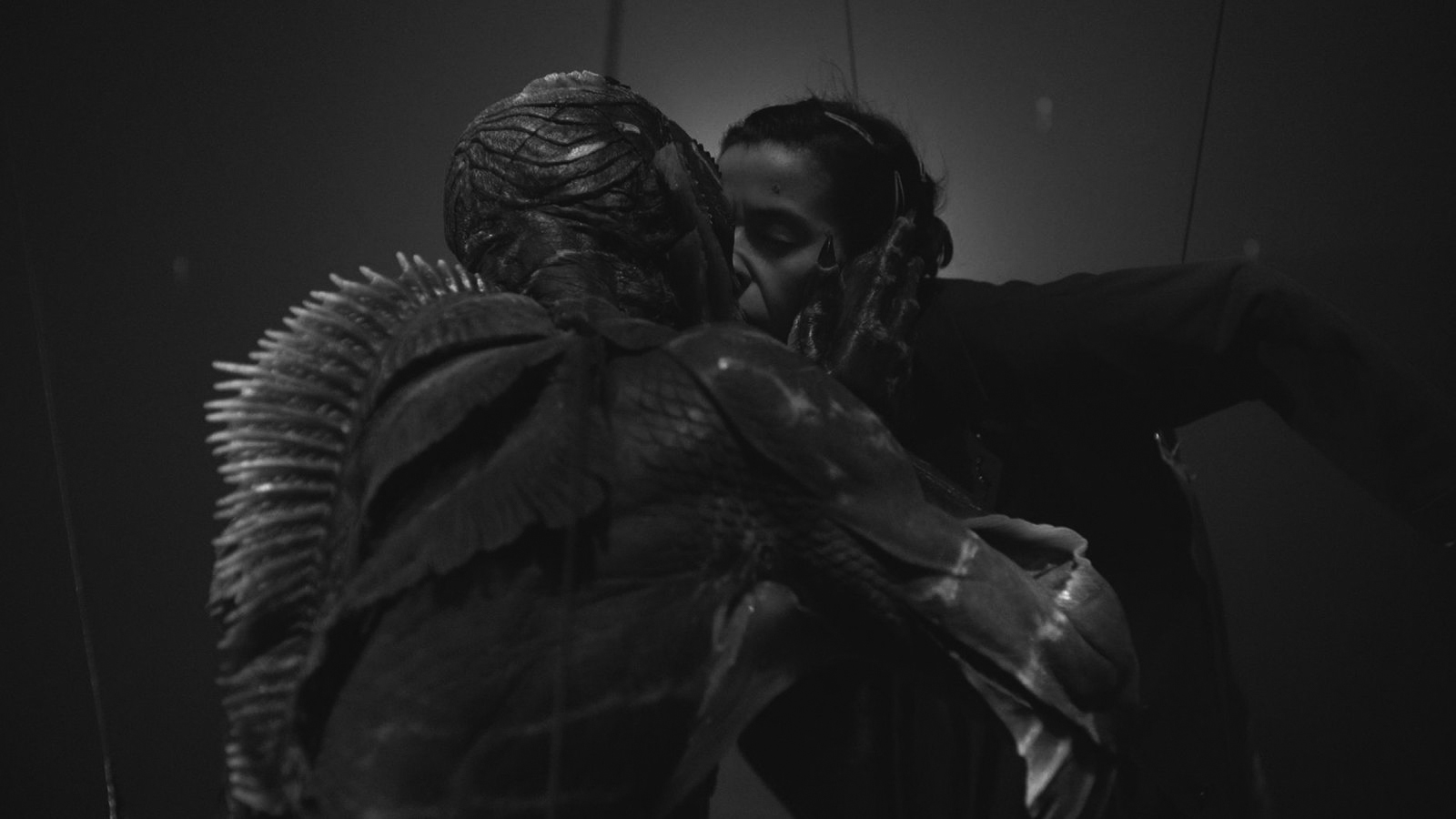

Seemingly half man, half amphibian, this being intrigues Elisa. As time passes, she begins communicating with the creature through American Sign Language. A codependency is formed. Alone, in the dark isolation of the lab, Elisa shares her favorite food, music and stories with the creature – in secrecy. For the first time, Elisa feels alive. As she asserts in one of the film’s most beautiful monologues, entirely in sign, the being sees Elisa for what she is, not what she lacks. Nobody else, despite the privilege humanity affords, seems capable of loving Elisa the same.

Much like the creature, Elisa hears, but cannot speak. They both feel hurt, love and loss just the same. And all those emotions come to a head in the film’s ultimate struggle.

As the plot progresses, the facility’s power-hungry supervisor – Col. Richard Strickland – hopes to kill the creature. A devout Christian, Strickland feels the being is anything but made in God’s image. And, while he asserts the creature as sacrilegious, it becomes evident that its unexplainable existence is simply an offence to Strickland’s narrow mindset.

In Strickland’s pursuit of preserving the obvious and rejecting inquisition, the creature is met with cattle prods, slurs, chains and shackles. All this abuse comes to fruition behind closed doors and pushes Hoffstetler towards facilitating a lethal injection. Elisa, “on duty,” lurks in the shadows, pressed by her humanity to intervene.

With the help of her roommate, Giles, and fellow janitor, Zelda (played by Octavia Spencer of “Hidden Figures”), Elisa helps escape the creature from the facility – housing him in her dated apartment’s bathtub.

Of course, the latter portion of the plot surrounds Strickland’s pursuit of the missing creature – coming to a head in a Romeo and Juliet-style ending, but the film’s engagement stretches far beyond these action-packed moments of anxiety in breaking the law for those one loves.

The film successfully juxtaposes Elisa’s undying pursuit of protection over the only being that understands her to a slew of 1960s zeitgeists that impact all the film’s main and supporting characters.

Zelda, a black woman, is consistently reminded by Strickland that she ought to feel lesser – not only because of her ancestry, but because of the untrustworthy biblical character that inspired her middle name, Delilah. Giles, a struggling gay artist, aims to find success in his work – always falling short because of the unappealing nature of his gayness at the time. His art and gayness alike are made a mockery and, at one point, he’s even thrown out of a coffee shop for advancing on a bartender who – despite making a “first move” on Giles – is able to more eloquently protect his identity.

Naturally, Elisa is the most persecuted of the bunch – without the ability to vocally stand up for herself and the creature she loves.

While Elisa’s growing draw to the creature served as a major point of controversy for the film, it’s a beautiful connection nonetheless. It’s in these intimate sub stories that viewers find relatability in that dynamic.

In a paramount moment, Elisa fully unstrips her worn heart and professes her love for the creature to Giles in sign, though he initally refuses to except the being’s humanity.

“I move my mouth like him,” she signs, eyes heavy and gasping for breath. “I make no sound like him. What does that make me?”

Elisa goes on, breathing mankind into what others see as a monster.

“All that I am – all that I’ve ever been – brought me here to him,” she continues. “…He does not know what I lack or how I am incomplete. He sees me for what I am.”

In that confession, the genius behind “The Shape of Water” is unveiled.

Each of the work’s characters finds his or her humanity in a humbling experience of, for a brief moment, being the bigot they’ve felt suppressed by. Zelda, Giles and, in her first encounters with the creature, Elisa, felt confused, bewildered and uncomfortable with the mystery that shrouds something so different. But that same predisposition to judgement of outside forces is precisely what has kept their own happiness at bay.

In the film’s closing moments, Giles narrates Elisa’s journey of self-actualization in having that chance to love the unloved – calling on a some hundred-year-old poem.

“Unable to perceive the shape of you, I find you all around me,” he reads. “Your presence fills my eyes with your love. It humbles my heart, for you are everywhere.”

“The Shape of Water,” a modern adaptation of the classic, Beauty and The Beast tale, traverses how we find our humanity in compassion for those inconceivably estranged.