Photo courtesy of Steven Stutz/The Bona Venture

stutza20@bonaventure.edu

BY CASSIDEY KAVATHAS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, and HADLEY THOMPSON, NEWS EDITOR

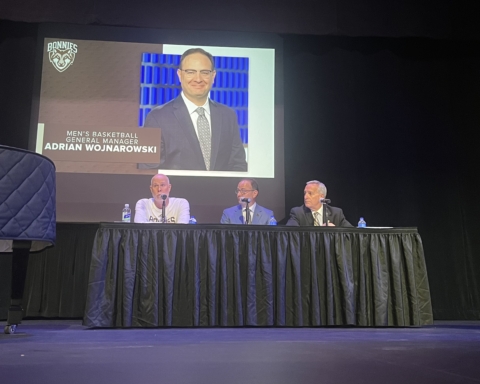

Jeff Gingerich, president of St. Bonaventure University, has been named a defendant in a civil lawsuit regarding alleged wrongful termination of an employee at The University of Scranton.

As provost at Scranton, Gingerich participated in the termination of Benjamin Bishop, a tenured computer science professor, on or about May 10. Bishop refused to disclose his COVID-19 vaccination status but was vaccinated.

On Nov. 16, Bishop filed the lawsuit in the U.S. District Court of the Middle District of Pennsylvania against Gingerich, Scranton and Scranton’s Faculty Affairs Council.

The counts, exactly as stated in the suit, include:

Count 1: Compulsion of political speech against University of Scranton

Count 2: Violation of the rights to body autonomy and found in the fourteenth amendment to the United States Constitution against University of Scranton

Count 3: Wrongful dismissal in violation of Pennsylvania public policy against University of Scranton

Count 4: Breach of contract against University of Scranton

Count 5: Violation of plaintiff’s rights to due process against University of Scranton

Count 6: Violation of the plaintiff’s rights to be free from selective enforcement against University of Scranton

Count 7: Defamation against University of Scranton and Gingerich

Count 8: Breach of duty of fair representation against University of Scranton’s Faculty Affairs Council

Jeffrey Sun, a lawyer and professor of higher education at the University of Louisville who is not associated with this case, has reviewed the lawsuit and is skeptical of the claims.

“[For] administrators at private universities, it’s much more contractual in nature. You’ve accepted the terms or not accepted the terms. There are disputes perhaps potentially on the contract side, but I will say that it doesn’t seem like this will prevail, given the nature of the suit being on the vaccination disclosure,” said Sun, an Education Law Association board member and a higher education scholar, in an interview with The Bona Venture.

The Education Law Association is a forum of current, aspiring or retired professionals involved in public and private K-12 or postsecondary education in legal practice in the area of education law.

Regarding the suit, Bonaventure released a statement.

“Neither the university nor Dr. Gingerich will comment on this matter,” said Tom Missel, chief communications officer.

Scranton also released a statement.

“The University of Scranton does not comment on pending litigation,” said Stan Zygmunt, a university representative.

The Scranton Faculty Affairs Council declined to comment.

“The basis of the suit is that Bishop believes his constitutional rights were violated,” Sun said

“That Scranton’s [COVID-19] mandate violates his constitutional rights,” Sun said, “it’s highly unlikely that’s the case.”

“People being concerned about bodily autonomy and medical privacy,” Bishop told The Bona Venture, is similar to post-COVID-19 issues across the country.

On Scranton’s website, there is a Pandemic Safety Non-Compliance Incident Form which encourages community members to report any acts violating the plan. Bonaventure also had a version of a non-compliance incident form; this became common among COVID-19 policies.

“They have this kind of ‘turn in your neighbor’ on a reporting form where they are asking faculty and students to turn in one another,” Bishop said. “That wasn’t really something that I wanted to be a part of.”

Scranton is a private university. In the suit, the plaintiff, Bishop, argues that Scranton became a state actor by following the guidance of government organizations.

If Scranton was a public university the constitutional-rights infringement argument would have more merit, Sun said.

“We can’t say, ‘just because there’s a health and safety code, or there’s a fire code or housing code that involves the federal government all the time, that means they’re acting on behalf of the government.’ They’re acting on behalf of laws that protect society. It’s not infringement of anyone’s constitutional rights,” Sun said.

Bishop said that it would be setting a bad example for his students if he complied.

“This is what the university said — that staff, administrators [and] faculty are expected to provide examples for students on compliance with the provisions of the plan,’” Bishop said. “Basically, it goes on to say if you don’t do that, you could be dismissed.”

Bishop said these issues are very prevalent in academia.

“Is it really ethical to be putting these vaccines into unwilling, healthy twenty-somethings when you have people in the developing world who might be 80 with diabetes or heart disease?” Bishop said. “Perhaps they want the vaccine, but they’re not able to get it because of decisions that we’re making here.”

Sun said that only the government can interfere and violate constitutional rights, but — because Scranton is a private industry — it can do things that a public university could not.

“He’s [Bishop] claiming that Scranton acted on behalf of the government and is politicizing this whole issue,” Sun said. “The irony of this whole thing is the person who’s suing is the one who’s politicizing it, not the university … What rights then are we saying about the people who want to be protected by health and safety. And he’s not helping [to] adhere to that.”

Bishop said that his issue with Scranton is the implementation of the Royals Back Together Policy, an approach to health and safety guidelines recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The plan also included a vaccine mandate.

Any example set for students is a choice of academic freedom, Bishop said.

“I’ve got students that are going to go off to defense contractors,” Bishop said. “I’ve got students that are going to work for government agencies, and I don’t want to set the model for them of blind obedience to their employer.”

Bishop said that if there is an unethical policy, he would rather teach his students to view it objectively.

“What example do you want to set for the students?” Bishop asked.

In his case, Bishop said Scranton allowed him to teach in person for part of the pandemic because it was hard to adapt the course to remote instruction. When he was banned from campus, it caused a crisis for students in the middle of those courses.

“They substituted these other faculty that really didn’t have time to prepare for the course,” Bishop said. “It led to a pretty difficult transition.”

To Bishop, the financial compensation of the lawsuit is secondary.

“There is a lot of opportunities in my field,” Bishop said. “If I was only interested in money, I probably wouldn’t have gone into teaching to begin with.”

Bishop said he is focused on transparency.

“Maybe some policies were implemented in reasonable ways, but — in this case — I think this is a situation where COVID-19 is being used as a pretext to fire critics of the administration,” Bishop said.

The evidence is compelling and obvious, Bishop said. Though the lawsuit is related to Gingerich personally, Bishop is one of three critics that was forced out of Scranton, he said.

“The policy is being enforced selectively,” Bishop said. “In the statement of charges, when they charged me with professional misconduct, they basically said that you are charged with violating the Royals Back Together Plan.”

Bishop said that Gingerich has also violated the plan.

“There are photos of him on campus, unmasked, in violation of the policy, and he admitted to that,” Bishop said.

In Exhibit F of the lawsuit, Gingerich admits to violation of the policy over email to Nathan Lefler, a professor of theology and religious studies at Scranton.

Bishop cited Gingerich and Scranton for alleged defamation of his character before and after his termination.

Sun believed that Scranton was replying to Bishop’s comments.

“The defendants in this case, the university and the provost, were responding to him, the plaintiff, and what he was doing. It doesn’t mean that they have publicized it. So, unless there’s evidence that it’s been so-called ‘published’… and it’s not in response to what he is saying … because it seems like it’s been instigated by him,” Sun said. “The plaintiff opened the door and was making these comments. It doesn’t seem like there’s anything here.”

The defamation would have to be published in a public outlet such as a newspaper.

Bishop said that he understood Scranton’s actions.

“For a critic, we’re gonna fire him,” Bishop said. “But if you happen to be provost, well, it’s no big deal,” Bishop said.

There is a disciplinary hearing that happens when a tenured professor is fired, Bishop said.

The faculty handbook at Scranton states that a tenured full professor could only be terminated for “financial exigency, discontinuance of a program, national emergency or major catastrophe or dismissal for adequate cause,” according to the suit. Sun said that this is a typical phrase used by many universities regarding the process of terminating tenured professors.

“It doesn’t mean you can’t terminate tenured faculty members — as much as people think it’s impossible to terminate a tenured faculty member. You can terminate them. It’s just that they have rights to what we refer to as ‘due process,’” Sun said. “You have to follow their due process. You can only do it under these conditions, and you have to follow certain rights of how you file and give them notice of what they did wrong.”

Sun believed the reason for Bishop’s termination falls under adequate cause.

“The adequate cause that the university is suggesting — and whether it could do this or not is not clear to me — is for failing to adhere to university policy. The university policy is that he’s failing to demonstrate proof of his vaccination. So, if that truly is the policy, then the answer is yes, it [is] likely they could do that,” Sun said

Though Bishop did not disclose his vaccination status to Scranton, resulting in his termination, he did disclose his vaccination status in Exhibit C.

“It has been decided in several jurisdictions that asking for health and safety such as vaccines is not necessarily overly intrusive. And failure to disclose that you’ve gone through proper approaches is not too invasive. It’s not too intrusive,” Sun said. “He has an option. I think there’s an opt out period to where he can opt out if he has something like a religious [reason] or other reason. He never forwarded any of those reasons.”

Bishop claims he was excluded, in-person and remotely, from the disciplinary hearing for health and safety reasons.

“If you think of that from a health-and-safety perspective, there is no justification for that,” Bishop said. “I am not gonna spread COVID-19 through Zoom or something.”

But if the institution was trying to avoid criticism, he said, it is understandable as to why he was excluded.

Bishop said there was a false claim, made by Gingerich, that he was endangering the health and safety of campus. He then showed a picture of Gingerich at an indoor Scranton fellowship event on Feb. 10.

“That right there, that’s your university president standing in front of a crowd during a mask mandate just flagrantly violating his own policy,” Bishop said.

The lawsuit asks that Bishop be reinstated to Scranton. He said in an ideal world, he would like to be reinstated, but he does not know if it is practical.

“This is after about a year of false … criminal allegations [saying] that I endangered the safety of campus,” Bishop said. “If I were to go back to Scranton, is it really feasible to do?”

Bishop said that he is still forbidden from coming on campus.

“Apparently, I’m such a danger that I can’t go onto campus,” Bishop said.

Bishop said that regardless of how the lawsuit turns out, he finds the publicity surrounding the issue is important for accountability.

“I don’t think in academia you want a situation where faculty are fired secretly,” Bishop said. “I think that there should be some sort of debate, discussion … I think it’s healthy in that sense.”

Sun believes that the suit will likely fail “for two major reasons.”

“One reason is because he’s suing under constitutional claim, and Scranton is a private university. Likely, he will not be able to show that Scranton acted on behalf of the government. But, on top of that, there is likely no constitutional rights that have been violated to begin with,” Sun said. “… Based on my review here, it’s highly unlikely that he will prevail. Also, on the contract law, there is a provision [that] tenured faculty members may be dismissed for adequate cause when the faculty member has failed to comply with university policies.”

Administrators are placed in a tough spot regarding how to address COVID-19 because it is a community-spread virus, Sun said.

“The university will be sued for not doing something, too. A tough situation that administrators have to balance nowadays — they have to make the decision, and they have to make it while … they still have to make it fairly quickly. Because there’s other people on the other side who are pushing and pressuring them to make a decision,” Sun said.

Sun says that the suit goes back to one main question.

“Whose rights are we protecting? And what are we doing? We’re unveiling people to this potential harm, because this individual didn’t want to disclose it because he wanted to prove a point,” Sun said. “I think one thing that we have to talk about and have to really address is how vaccines and other things have been politicized.”

kavathcj20@bonaventure.edu

thompshp20@bonaventure.edu